Are You Really Ready for Christmas?

Advent is a time for us to return to what this season—and our lives—are to be about: worship. Not just for Advent, but for always.

Surely by now you’ve been asked, “Are you ready for Christmas?” By which we generally mean, “Do you have all the presents bought and wrapped, all the decorations hung, all the food bought, and all the other to-dos crossed off your list?” We know we need to be prepared for something—but what?

Most often, we assume we are to be ready for that magical moment of Christmas morning when we gather around the tree and distribute gifts to our loved ones.

Like me, you might find yourself asking, “Is that what it’s really about?” Your gut tells you you’re somehow missing the mark.

CHRISTMAS BEGINS AT AN ALTAR

Thankfully, Scripture gives us a clue as to how God wants us to prepare for Christmas. We need look no further than the surprising beginning of the Christmas story. We presume the opening scene to be of a Jewish man carefully accompanying his donkey-riding, full-term fiancée through a snowstorm to the Little Town of Bethlehem.

But the Christmas story actually begins about fifteen months earlier with an elderly, childless couple—not a couple waiting for the arrival of a baby, but a couple defined by waiting for a child, and welcoming none (see Luke 1:5-25).

Zechariah and his wife Elizabeth are descendants of Aaron, the first Jewish High Priest, and are described as “righteous before God, walking blamelessly in all the commandments and statutes of the Lord” (Luke 1:6). As a priest, Zechariah served regularly at the temple, a responsibility he’s fulfilling when an angel suddenly appears to him.

The location of this angelic appearance does not happen by chance. Gabriel could have appeared to him at home, while he was working in the field, or during a long journey. However, God intentionally chose to reveal his plan to Zechariah while he is in the temple, at the altar. God intentionally brought his first Christmas announcement in the place of worship, alerting us that this is a story about worship.

ISRAEL’S WORSHIP PROBLEM

Israel had a long history of cluttered altars. The people had often abandoned the God who redeemed them and made them his own special people. Such a great beginning makes it all the more tragic when their story consistently turns towards rebellion, rejection, and idolatry. They regularly turned their back on God and literally cluttered their altars with idols and false gods (e.g. 2 Chron. 33:4-5). They habitually adulterated their worship and kept God at bay by filling their lives and altars with other things.

When Zechariah the priest entered the temple to burn incense, he was, essentially, leading the nation in worship (Luke 1:10) and representing them before God. Even though he is described as righteous and blameless, he belongs to a people who have constantly been mired in idolatry, confusion, and waywardness. They are turned away from God, in conflict with each other, ignorant of God’s ways, and walking in disobedience.

Israel’s worship problem is the context of the angel Gabriel’s announcement.

WE HAVE A WORSHIP PROBLEM, TOO

Like the Israelites of old, we too have a worship problem. And Jesus has come to solve it. Thus the angel Gabriel’s announcement to Zechariah, declaring the work that his future son, John the Baptist will accomplish:

“And he will turn many of the children of Israel to the Lord their God, and he will go before him in the spirit and power of Elijah, to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the disobedient to the wisdom of the just, to make ready for the Lord a people prepared” (Luke 1:16-17).

John’s job will be to go before Jesus and bring about a threefold turning. The first turning was repentance, turning “many of the children of Israel to the Lord their God,” away from the idols that clutter their altars. The second turning was reconciliation, turning “the hearts of fathers to their children.” When God makes people right with himself, he also does the work of making them right with one another. The third turning was transformation, turning “the disobedient to the wisdom of the just.”

The Bible regularly juxtaposes the wise and the foolish. The wise are just, righteous, and obedient, while the foolish are unjust, wicked, and disobedient. God is in the business of making foolish men wise, and disobedient men just (see Jer. 31:33-4; 32:36-41; Ezek. 36:26-27).

WHAT WE’RE PREPARING FOR

Ultimately, John’s job would be “to make ready for the Lord a people prepared” (Luke 1:17). But prepared for what?

Two connected passages give clarity on the purpose of this preparation as well as insight into the purposes of our own Advent preparations; that we are to be prepared to see God’s glory and respond in worship.

Prepared to see God’s glory. Isaiah lined out a job description for John the Baptist hundreds of years before his birth:

“A voice cries: ‘In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord; make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain. And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together, for the mouth of the Lord has spoken’” (Is. 40:3-5).

The metaphor is that of a cluttered path—valleys, mountains, and the uneven, rough ground that marks the difficult paths of the world and of our lives. These are the paths we create on our own, attempting to walk them without God. It is a path for God, yet we are the ones who’ve cluttered it! John’s job was to be an earth-mover; to run a spiritual bulldozer over these self-made roads and level out a path upon which God himself would come to his people.

The path that John was to prepare (and that Advent mimics, in a way) was a path of welcome. It was the path of the King, upon which we are to roll out the red carpet in welcome. Advent is a time of preparation for welcoming the King!

The ultimate purpose of this leveling work is “for the glory of the Lord [to] be revealed and all flesh [to] see it together” (Is. 40:5). God is making it possible for us once again to clearly see His glory. In order for that to happen, the path has to be cleared. It has to be decluttered.

Prepared to respond in worship. When John is born, Zechariah’s mouth is opened for the first time in nine months, and he sings a song of praise to God. In it, he prophesies to his son, “And you, child, will be called the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give knowledge of salvation to his people in the forgiveness of their sins” (Luke 1:76-77). All this, Zechariah says, so that the people might “serve him [i.e., worship God] without fear, in holiness and righteousness before him all our days” (Luke 1:74-75).

As a descendant of Aaron, John too was a priest. His would be preparatory in nature: cleaning house, decluttering, and removing obstacles so that nothing else would distract from what Israel was made for: to worship God.

So, what are we preparing for during this Advent season? We are preparing to worship.

ADVENT: A SEASON TO DECLUTTER

Advent is a season meant to prepare a people for the coming of the King. It’s a time of decluttering from all the things we’ve thrown into the path and onto the altar that bog down our worship, replaced Jesus in our affections, and distracted us from him.

Advent is a yearly rhythm of intentionally entering into practices that help us to declutter our spaces, calendars, wallets, minds, and hearts. It’s a time to intentionally get our house ready for the one who came as a baby. Decluttering is an act of hospitality, of rolling out the red carpet, of preparing, and of going all out in order to make room for and welcome the King.

Advent is a time for us to return to what this season—and our lives—are to be about: worship. Not just for Advent, but for always.

Mike Phay serves as Lead Pastor at FBC Prineville (Oregon) and as a Staff Writer at Gospel-Centered Discipleship. He has been married to Keri for over 21 years, and they have five amazing kids. You can follow him on Twitter (@mikephay) or check out his blog.

You Become What You Trust

Humans have always loved idols. Israel’s history shows us that no matter how many miraculous wonders we witness, our hearts will always elevate the created before the Creator (Rom.1:25). What began as statues to Baal, Asherah poles, and Greek temples, continues to permeate our culture. These days, our idols look a bit nobler—a spouse, children, happiness, comfort, health—but they enslave us just like the idols of old.

Our idols don’t just settle for helping us break the second commandment, they permeate much deeper in our lives. The Psalms tell us that those who trust idols will become like them (Ps. 135:18). We may not turn into stone and wood, but eventually, the idols of our heart can chip away at significant areas in our spiritual lives.

The idols we create are blind, deaf, and mute, and if we continue serving them, we’ll eventually become the same. If left undisturbed and ignored, we may begin to lose our own sight, become deaf to others, and render our speech useless to the surrounding world.

Blind to Our Sin

One of the first ways we become like our idols is in becoming blind to our own sin. If we are in Christ, we have been given a new heart (Ezek. 36:26) and our eyes are opened to the gospel, yet the temptation to turn back towards darkness endures. It’s why the author of Hebrews exhorted the church to take care that no one has an unbelieving heart, “leading you to fall away from the living God” (Heb. 3:12-13).

Each person, feeling, circumstance, or dream we hold up as more important than God is ultimately a declaration of unbelief. Our idols make us believe that God won’t satisfy more than our they can. Our idols make us think that God’s grace isn’t enough, so we must make our own rules. They make us think that seeking our own comfort is more worthwhile than seeking the Lord’s glory.

We may not say these truths out loud, but the subtle deceitfulness of sin (Heb. 3:13) will continue to feed our idols of unbelief, make excuses, and harden us to the sin we harbor. Some of us may continue to idolize health, blind to the ways we are trusting in our workouts to give us the peace that only God can give. Others may cloak our approval-seeking in righteous words like service or encouragement, but in reality, our idols stay hidden behind the sin we can’t see.

The trouble is, we can’t crush what we can’t see. This is where the passage in Hebrews gives us great hope. We must “exhort one another daily” (Heb. 3:13). Just as we could not open our eyes to Christ without his work, we need the Holy Spirit and Christ’s church to open our eyes to our blindness—even after salvation. It’s our brothers and sisters who can illuminate the darkness, and the Holy Spirit alone who can give us back our sight and put to death the idols of unbelief in our hearts.

Deaf to Our Brothers and Sisters

Our idols can make us become blind to our own sin, but they can also cause us to become deaf to our brothers and sisters in Christ. We see this played out in big and small ways in the church, whether it’s the prideful parent who refuses to seek any outside help, or the church member holding his politics so tightly that he can’t hear the concerns of a brother in Christ. Our strong opinions, steeped in the idolatry of self, can keep us so attuned to our own views that we can’t stop to give grace or charity to our dissenter.

But Christ calls us to something radical. He not only tells us to open our ears but to go even further by outdoing one another with honor (Rom. 12:10). We are told to bless those who hurt us, to be humble in our own eyes, and do what is honorable in the sight of all (Rom.12:14-17).

Beginning to knock down these idols begins by first finding the root. Where are we deaf to the concerns and wisdom of our brothers and sisters in Christ? What topics do we bristle at hearing a word of correction? Or what topics do we refuse to seek wisdom in?

You’ll likely have to ask a trusted brother or sister to help you see what you cannot. Of course, our brothers and sisters in these disagreements are sinners too, but Jesus tells us our first step is always to look upon our own sin (Matt. 7:3).

Mute to the World

Finally, our idols can mute our voice to the world around us, which fleshes out in two ways. The first is seen when our idols make us look exactly like the world around us. When we idolize comfort, a job, or happiness, we will inevitably be tossed into anxiety when these idols are not met. When the job is lost or life gets difficult, we will look no different than the unbeliever in the cubicle sitting right to us.

As Christians, however, our lives should look different because our hope is completely different. That doesn’t mean that we can’t feel stressed or experience difficulty, but it does mean that our priorities should look different than the unbelievers around us. When we continue to let the idols of our hearts take over, they rob us of the chance to preach a different and beautiful story to the world around us.

Secondly, our idols keep us from purposefully entering into the lives of those around us. Who has time to develop a relationship with a neighbor when we are too busy with our own projects? How do we encourage the woman behind us in the checkout when we are too concerned with our phone? The nature of man-made idols is that they must be maintained. We must keep feeding our need for approval, tone our body, multiply our entertainment—and when we do we are left with little time for else.

But again, Jesus calls us to something radical. We have a different mission than maintaining our idols. Instead, we are to give up our hold on everything in this world to gain everything in the beauty of Christ. We are to make disciples (Matt. 28:19-20) and to proclaim his name among the people God has put around us. And if we want to be ready to give an answer for the hope we have in Christ (1 Pt. 3:15), we must first clear away the idols that rob us of that voice.

Good News for Idolaters

While it’s painful to see the grip of idolatry, the good news is that we worship the God who stands above every idol. Just as the ancient statue of Dagon fell to the ground before the Ark of the Covenant, our own idols will fall prostrate before the true God of heaven (1 Sam. 5:2).

We don’t have to feel defeat but can seek out our idols so we can destroy them. We can stop to see what has been keeping us from speaking the gospel to those around us. We can ask God to show us where our ears have been closed to our family in Christ. And we can ask from the Holy Spirit and our brothers and sisters to help show us the sin we can’t see.

We may start to become like our idols, but it’s the power of the cross—the same power that raised Jesus from the dead—that gives us the power to crush them. Each day we can lean on the God who continues to breathe life and hope into our blind, deaf, and mute hearts.

Brianna Lambert is a wife and mom to three, making their home in the cornfields of Indiana. She loves using writing to work out the truths God is teaching her each day. She has contributed to various online publications such as Morning by Morning and Fathom magazine. You can find more of her writing paired with her husband’s photography at lookingtotheharvest.com.

Learning to Live in This Home Away from Home

If you’re a Christian, you’re a miracle. Your conversion was a restoration of fortunes, a miraculous release from captivity, and a joyful homecoming. With God, there are no “boring” testimonies. But over time, life gets boring. We wonder how we lost that lovin’ feeling. We want the good times back. More than that, we want a future of greater glory.

Israel anticipated the hopeful restoration of Zion. But they didn’t just hope for a prosperous city—they looked forward to a reigning king, their promised Messiah.

They looked forward to the time when, after the anticipation and the hope, after the promises and the prophecies, Jesus comes. He lives and dies and rises again to save his people from their sins.

But that’s not the end of the story. The Bible concludes not with a deep sigh of rest but cries out in desperate anticipation, “Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev. 22:20). God’s people aren’t home just yet.

Such is the tone of Psalm 126, a psalm of ascent, filled with what was and longing for what will one day be.

LONGING FOR BETTER DAYS

Even without knowing much of the context, it’s easy to see that Psalm 126 speaks of an Israelite restoration so grand that even the surrounding nations remembered it (Ps. 126:2-3). Maybe it was their return from exile in Babylon. Maybe something else.

Whatever it was, it was like a dream (Ps.126:1). It was the happy day from which all others orbited, evoking laughter and joy, like Job after his suffering (Job 42:10). And the psalmist wanted another hopeful and joyous restoration.

Christians recognize this feeling of elation. Like the conversion experience or a season of personal revival, spiritual restoration awakens zeal for the gospel. These brief moments can stick in our memories for a lifetime, and if you’re like me, are ones to which your heart longs to return.

The psalmist understood that longing. The Lord had done great things for the people of God, and they were glad (Ps. 126:3). But that gladness faded, as it tends to do. We need more than memories of great things done. We need the hope of great things to come.

NOSTALGIA ROAD

An initial reading of this psalm can leave the reader with the impression that nostalgia weighed the psalmist down—like remembering “the good ole days” that are now long gone. But that’s not quite the tone.

Nostalgia takes us half-way home; it takes us back to the place of our former blessing, but it can’t take us to future hope. Like the glory days of old, only God can take us to that blessed shore. Only God can gather us together with lasting joy, like Israel bringing in plenty during the harvest (Ps. 126:5-6).

“Nostalgia” first appeared as a word in the 1770s, springing from the combination of the Greek words nostos, meaning “homecoming,” and algos, meaning “pain.” In the 1800s, encyclopedias of medicine listed nostalgia as a disease: “severe homesickness.”

Isn’t that what we all are, to some degree or another? Homesick.

Israel sure was, even at home. So are we. We’re homesick for God, for what only he can provide. We’re homesick for final freedom, forgiveness, refuge, victory, and peace.

Christians live in a world that looks like home without the satisfaction of home. As C.S. Lewis said, “If we find ourselves with a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that we were made for another world.” Made for another world, indeed. But we’re in this one now, and we must learn to live here.

LEARNING TO LIVE HERE

Far from a disease bringing one down, the memory of Psalm 126 causes the careful reader to swell with hope. Today may not be like yesterday, but God doesn’t intend to take us back to what was. He intends to bring us forward to what will one day be.

The Garden of Eden was a pointer to—not the culmination of—the glory to come. God’s gift of your future is better than the varied gifts of your past. In the end, even all the revivals of history will pale in comparison to the great revival coming on the clouds. Walking with Jesus is a journey of hope!

So Psalm 126 is not a great and longing sigh as much as it is the first verse of a new and hopeful song. Yes, there is a plea for restoration (Ps. 126:4), but it’s not a cry of desperation. It’s a cry of expectation. It’s a cry for God to do it again, grounded in faith that he will.

The lesson is that learning to live here is more than coping with a happy memory, it’s rejoicing in a coming glory. That doesn’t mean homesickness is easier to bear. It means, given to Christ, nostalgia points us homeward to glory rather than backward to the Garden.

Jesus reverses nostalgia’s direction. With him, as good as our past was, the best is yet to come.

THE GARDEN OF GRACE

However, the glory to come doesn't make the present angst disappear. Life is full of disappointments. So God gave us the Psalms—as Tim Keller says[i]—to pray your tears (Ps. 126:5-6).

No single event of blessing is enough to sustain us forever. We forget. We weaken. We falter. We fall.

We need a resurrection hope. That's why God sent his Sower to sow gospel seeds into our lives (Mark 4:1-20). But that seed doesn't grow instantly. Cultivating takes time we don’t often want to spend. It takes watering when we don’t want to. It takes, in a word, maturing.

Learning to pray our tears is the maturing process by which we prepare for a greater harvest. Psalm 126:5-6 promises “those who sow in tears shall reap with shouts of joy! He who goes out weeping, bearing the seed for sowing, shall come home with shouts of joy, bringing his sheaves with him.” As we weep toward God, he takes our tears and plants them in his garden of grace. They take root and grow. But the harvest comes later—as late as the resurrection.

SHOUTS OF JOY

I imagine Mary Magdalene and the other Mary on their way to the tomb of Jesus, weeping as they walk. What a joy it was to know him, to be by his side as he taught, as he healed, as he filled the world with happiness and hope. But that was yesterday. Today, their tears are with him in the grave, buried in the ground.

As they approach the garden tomb, the earth quakes and the stone rolls away. Someone stands before them. His appearance is like lightning. His clothing is white as snow. He seems to know their tears. “Do not be afraid, for I know that you seek Jesus who was crucified. He is not here, for he has risen.”

Could it be? Then behold—he appears and says, “Greetings!”

They fall and worship. Then they rise and go, to tell his disciples that they too will see him. (Matt. 28:1-10).

In other words, they’re coming home with shouts of joy (Ps. 126:6).

NO MORE TEARS

Sally Lloyd-Jones captures this joyful mood in The Jesus Storybook Bible. Mary runs,

And it seemed to her that morning, as she ran, almost as if the whole world had been made anew, almost as if the whole world was singing for joy—the trees, tiny sounds in the grass, the birds . . . her heart.

Was God really making everything sad come untrue? Was he making even death come untrue?

She couldn’t wait to tell Jesus’ friends. ‘They won’t believe it!’ she laughed.

She laughed. Oh, she laughed!

Her mouth was filled with laughter (Ps. 126:2) because the Lord had done great things for her (Ps. 126:3). But not only for her. The Lord had done great things for all his people, for all his friends, for all of us.

Those great things of the resurrection came by way of death. That’s the Christian life: first the cross, then the crown. It's the planting that produces the harvest, the death that produces life. As Jesus said, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24).

Jesus is the proof that buried hope grows into glorious reality. The tears of the cross bore the fruit of the resurrection. He went out weeping, bearing his life for sowing; he came home with sheaves (Ps. 126:6), bringing many sons to glory (Heb. 2:10).

COMING HOME TO A BETTER STORY

Israel’s story was a good one, but a better one was yet to come. And there’s a better one coming for us, as well.

One day, the Lord will restore our fortunes—untarnished communion with him, coram deo. The first earth will pass away, and the holy city, the New Jerusalem, will come down out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.

We will receive our glorified bodies on the new heaven and new earth. On that great and glorious day, God will say to all his people, “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man” (Rev. 21:1-4). He will wipe every tear from our eyes, and death shall be no more!

No more mourning. No more crying. No more pain.

The former things will have passed away.

We’ll finally be home.

David McLemore is an elder at Refuge Church in Franklin, Tennessee. He also works for a large healthcare corporation where he manages an application development department. He is married to Sarah, and they have three sons. Read more of David’s writing on his blog, Things of the Sort.

[i] Timothy J. Keller, “Praying Our Tears,” February 27, 2000, City Life Church, Boston, sermon, The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

Why Does God Permit So Much Evil?

God has all power and all knowledge and is second to none. No equals and no competitors. The fact that evil is rampant in his creation is no surprise to him. It’s there only by permission. Fromtime to time, evil may seem to be running wild, but in fact it’s always on a leash. And we should be grateful that we’ve never seen how bad it could become.

Exactly why God allows evil in his creation, he doesn’t bother to tell us, and he doesn’t need to. He is God. We can’t understand everything about God, but we have enough information to satisfy many of our basic questions. In many cases, God chooses to let us go through whatever evil or trouble we may be facing at the moment. He could have prevented it and allowed us an easy skate, rather than the tough slog some have to endure. He could end it entirely but probably won’t until he’s through using it for his purposes.

An Intruder in God's Good Creation

If we take a close look at both the Old and New Testaments, we notice something interesting about evil’s presence in the world. It is considered an intruder into God’s good creation but is allowed to prowl about for a time, and with a considerable degree of freedom. Yet it’s always within bounds.

Sometimes it may look as though it exceeds all limits, and whereas good often seems to run out of steam, evil seems never to tire. But just when we think God’s hands are tied, he yanks the chain and brings it to heel. He is ruler of all. Evil is evil and good is good, but whereas God never uses good for evil purposes, he often uses or blatantly exploits evil for good purposes. He does this by turning it upside down and inside out.

Sometimes it may look as though it exceeds all limits, and whereas good often seems to run out of steam, evil seems never to tire. But just when we think God’s hands are tied, he yanks the chain and brings it to heel. He is ruler of all. Evil is evil and good is good, but whereas God never uses good for evil purposes, he often uses or blatantly exploits evil for good purposes. He does this by turning it upside down and inside out.

The stories of the patriarchs in Genesis are wonderful illustrations of evil being exploited for good. One of the clearest pictures comes to us in the account of Joseph. Young Joseph is mistreated, violently abused, tricked, kidnapped, enslaved, falsely accused, and imprisoned. Yet every time he is kicked and abused, he is mysteriously bumped up one more rung of the ladder. He moves from the deep hole in the beginning of the story to the position of the prime minister of Egypt at the end.

God used all the evil directed toward Joseph as raw material to construct not only his preservation from starvation and death but also the rescue of those who abused him as well as the salvation of the entire nation he served. As Joseph says, “You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives” (Genesis 50:20).

This pattern presented early in the Bible became the blueprint for how God has chosen to deal with evil in his realm for the rest of history. He may permit a certain amount of wickedness to occur, but he always reserves the right to twist and use it for his own purposes. We see the same design in the New Testament.

What we see in Genesis continues throughout early church history, through the centuries of the martyrs, in the subsequent eras of the church, and up to the present day. This is God’s will for the remainder of time until he brings down the curtain and calls humanity to final judgment. After every tiny scrap of evil is dealt with in the complete justice and fairness of God, he intends to recreate a new heaven and new earth where evil is no longer even a possibility—where only goodness and righteousness will exist.

The manipulation of evil for good ends is one of the most exciting aspects of God’s program on earth. He uses the bad things around us in ways we couldn’t possibly expect. He brings good out of the bad not in spite of it but because of it.

The Grand Master

Let’s examine a very earthly and human analogy of this. For example, it’s common practice to exploit the intentions of others for our own ends in a variety of ways. Consider the game of chess. As the competition progresses, the better of the two players cleverly ascertains his opponent’s game plan. He has two options. He can block and frustrate the plan immediately, or he can so arrange his own strategy to account for it, to absorb it. In this way, while his opponent is cheerfully fulfilling his own scheme, he’s also unwittingly fulfilling that of the superior player.

Just when he thinks he’s about to proclaim victory, he’s suddenly checkmated. The game is over.

So it is with God. He’s the Grand Master of chess, who can at any moment impose his own plan over ours (or anyone else’s), so that no matter what, he can bring the game to his own decreed conclusion. We may deliberately live a life of rebellion and selfishness, discarding his will at every point, or we may live a life of Spirit-empowered obedience and self-sacrifice. Whichever course we take, he wins in the end. By scripting his own plot to overarch ours, he allows us to fulfill our plans but ultimately to bring about his will. In this way, evil is both exploited as well as judged, good is rewarded, and God is the victor.

Of course, this is not a perfect analogy, since there are no exact earthly parallels to how God’s nature and sovereignty are involved in human life. God is entirely unique and profoundly mysterious. He is revealed to us only in part. As I said, this revelation isn’t everything we want to know, but it’s enough to grasp the basics of what he wants us to know. The main point of comparison here is that the superior being uses the activities of the inferior for his own will.

Over the years, our family has discovered that some of the best things that ever happened to us came as a direct result of the worst things that ever happened to us. If we take the apostle Paul seriously “that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose” (Romans 8:28), then we’ll eventually see how God still writes his superior, more sophisticated script over all others.

No matter what evils befall us, good (even excellence) may be brought out of them. This is one of God’s favorite things to do. This point is too important to pass over lightly.

And we need to remember, just as it is Satan’s purpose to take all that is good and turn it toward evil ends, so it is God’s purpose to take all that is evil in the lives of those who love him and turn it for good. The commandeering and exploitation of evil for good is one of the most powerful aspects of God’s strategies on earth. He skillfully manipulates the bad things around us in ways we couldn’t possibly expect or imagine.

A Truth We Need to be Fixed in Our Minds

We need to fix this truth in our minds. Between now and the final act of history’s play, God has determined to allow evil to roam about on a chain, not free to do anything and everything it wants, but to do much that we wouldn’t want. Evil will always be an intruder and an invader. As long as we dwell on this planet, we’ll always live in occupied territory. Evil will be relatively free (within God’s prescribed limits), but it will always be under the ongoing judgment of the Ruler of all things. Each and every day he will choose to exploit what evil determines to do and to turn it toward his good purposes.

Again, evil will continue to accuse, blame, abuse, misrepresent the truth, destroy, and pillage, but it will remain on a leash. It will never be totally free and will do no more than it’s allowed to do. God defeats it handily, takes it prisoner, and redirects it to bring the good he intends.

Why do I repeat myself? Simply to underscore this critical point: whether people choose to do evil or good in this life, God has decreed that he will write his will into the script of human history and bring it to its conclusion in exactly the way he has purposed.

We can oppose God’s will and do the most terrible things, or we can do everything in our power to try to please him. In either case, he’s able to enter into our own worldly troubles and sins and in some mysterious way bring out of them ultimate good—both his and ours. Without doubt, evil, and all those who love it and are given to it, will face judgment and destruction. But it is to God’s glory that we turn from it and live.

Taken from Resenting God: Escape the Downward Spiral of Blame, (c) 2018, Abingdon Press.

Dr. John I. Snyder is author of Resenting God and Your 100 Day Prayer. As an ordained Presbyterian pastor, John has served congregations in the United States and planted churches in California and Switzerland. He is the advisor and lead author for theology and culture blog Theology Mix (www.theologymix.com), which hosts 80+ authors and podcasters and visitors from 175 countries. He received his Doctor of Theology degree magna cum laude in New Testament Studies from the University of Basel, Switzerland. He also has Master of Theology and Master of Divinity degrees from Princeton Theological Seminary in Princeton, New Jersey.

This is What Intimacy with God Looks Like

It was not enough for God to make us his children. He wants us to know that we’re his children. He wants us to experience his love. And that’s why he sent the Holy Spirit. Galatians 4:6 says, “And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts.” The reason why God sent the Spirit is so that we can experience what it is to be sons and daughters loved by our Father. And notice how the Spirit is described. Most of the time in Galatians Paul simply refers to “the Spirit.” Often in the New Testament he’s described as “the Holy Spirit.” But here Paul calls him “the Spirit of his Son.”

Our experience of the Spirit is the experience of the Son, for the Spirit is the Spirit of the Son. The Spirit enables us to experience what Jesus experiences.

God Sent the Spirit of His Son So That We Might Know That We Are Sons

So the Father has given us the Spirit of his Son so that we can enjoy the experience of his Son, so that we know what it is to be sons like the Son, so that we can enjoy the love the Son experiences from the Father.

So the Father has given us the Spirit of his Son so that we can enjoy the experience of his Son, so that we know what it is to be sons like the Son, so that we can enjoy the love the Son experiences from the Father.

God gave his Son up to the whip, the thorns, the nails, the darkness, and the experience of forsakenness so that you could be his child. No wonder he sends the Spirit of his Son. He doesn’t want you to miss out on all that the Son has secured for you. This is his eternal plan: that you should enjoy his fatherly love.

The world is full of people searching for love and intimacy. Many sexual encounters and affairs are a desperate attempt to numb a sense of loneliness. Many people who seem to have it all feel empty inside. The actor and director Liv Ullmann once said, “Hollywood is loneliness beside the swimming pool.” We were made for more. The reason why we yearn for intimacy is that we were made for intimacy: we were made to love God and be loved by him. And this is what the Father gives us by sending his Son and by sending the Spirit of his Son.

What Does This Intimacy Look Like?

We Can Talk to God Like Children Talk to Their Father

“The Spirit . . . [cries], ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal. 4:6). The Spirit gives us the confidence to address God as our Father. A number of our friends have adopted children. And it’s always a special moment when the adopted child starts calling them “Mom” and “Dad.” God is infinite, holy, majestic. He’s a consuming fire before whom angels cover their faces. He made all things and controls all things.

Can you imagine calling him “Father”? Of course you can! You do it every day when you pray—most of the time without even thinking about it. How is that possible? Step back and think about it for a moment, and you’ll realize what an amazing miracle it is that any of us should call God “Father.” But we do so every time we pray, through the Spirit of the Son. This is how John Calvin puts it:

With what confidence would anyone address God as “Father”? Who would break forth into such rashness as to claim for himself the honour of a son of God unless we had been adopted as children of grace in Christ? . . . But because the narrowness of our hearts cannot comprehend God’s boundless favour, not only is Christ the pledge and guarantee of our adoption, but he moves the Spirit as witness to us of the same adoption, through whom with free and full voice we may cry, “Abba, Father.”[1]

Think of those adopted children saying “Mom” and “Dad” for the first time. What must that feel like for them? Perhaps they do so tentatively at first. They’re still feeling their way in the relationship. And that’s often what it’s like for new Christians, feeling their way in this new relationship.

But think, too, what it means for the parents. It’s a joyful moment. It’s a sign that their children are beginning to feel like children. It’s a moment of pleasure. And so it is for God every time you call him “Father.” Remember, he planned our adoption “in accordance with his pleasure” (Eph. 1:5 NIV).

We Can Think of God Like Children Think of Their Father

“So you are no longer a slave, but a son” (Gal. 4:7). Slaves are always worried about doing what they’re told or doing the right thing. They fear the disapproval of their master because there’s always the possibility that they might be punished or sacked. Children never have to fear being sacked. They may sometimes be disciplined, but as with any good parent, it’s always for their good. God is the best of parents. And we never have to fear being sacked. You can’t stop being a child of God—you’re not fostered. You’re adopted for life, and life for you is eternal!

The cry “Abba! Father!” is not just for moments of intimacy. It was actually the cry that a child shouted when in need. One of the joys of my life is that I’m good friends with lots of children. Charis always cries out, “Tim!” when she sees me. Tayden wants me to read his Where’s Wally? book with him. Again. Tyler wants me to throw him over my shoulder and swing him around. Josie wants to tell me everything in her head all at once in her lisping voice. They all enjoy having me around. But here’s what I’ve noticed.

Whenever any of them falls over or gets knocked, my parental instinct kicks in, and I rush to help. But it’s not me they want in those moments. They run past me looking for Mom or Dad. They cry out, “Dad!” and Tim won’t do. That’s what “Abba! Father!” means. When we’re in need, we cry out to God because the Spirit assures us that God is our Father and that our Father cares about what’s happening to his children.

We Can Depend on God Like Children Depend on Their Father

“And if [you are] a son, then [you are] an heir through God” (Gal. 4:7). When Paul talks about “sonship,” he’s not being sexist. Quite the opposite. In the Roman world only male children could inherit. So when Paul says “we” (“male and female,” 3:28) are “sons,” he’s saying that in God’s family, men and women inherit. Everyone is included. And what we inherit is God’s glorious new world. But more than that, we inherit God himself. In all the uncertainties of this life, we can depend on him. He will lead us home, and our home is his glory.

What could be better than sharing in the infinite love and infinite joy of the eternal Father with the eternal Son? Think of what you might aspire to in life—your greatest hopes and dreams. And then multiply them by a hundred. Think of winning Olympic gold or lifting the World Cup. Think of being a billionaire and owning a Caribbean island. Think of your love life playing out like the most heartwarming romantic movie. Good. But not as good as enjoying God.

Or let’s do it in reverse. Think of your worst fears and nightmares: losing a loved one, never finding someone to marry, losing your health, not having children. Bad! But Paul says, “I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us” (Rom. 8:18). The only time Jesus is quoted as saying, “Abba, Father,” is in the Garden of Gethsemane as he sweats blood at the prospect of the cross (Mark 14:36). Even when you feel crushed by your pain, God is still your Abba, Father.

Where does joy come from? It comes from being children of God. How can we enjoy God? By living as his children. How can we please God? By believing he loves us as he loves his Son.

[1]John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles, Library of Christian Classics 20–21 (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1960), 3.20.36–37.

Content taken from Reforming Joy: A Conversation between Paul, the Reformers, and the Church Today by Tim Chester, ©2018. Used by permission of Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers, Wheaton, Il 60187, www.crossway.org.

Tim Chester is a pastor of Grace Church in Boroughbridge, North Yorkshire, and a faculty member with the Acts 29 Oak Hill Academy. He was previously research and policy director for Tearfund and tutor in missiology at Cliff College. Tim is the author of over thirty books, including The Message of Prayer, Closing the Window, Good News to the Poor, and A Meal with Jesus. Visit Tim’s website and read his blog or follow him on Twitter.

What's in a Name? For Christians, Everything

I resent my childhood nickname. My childhood wrapped up in the 1980’s, so naturally, the film Karate Kid enthralled me. Convinced I could take on the bullying hordes of my second-grade existence, and wanting to establish that you shouldn’t mess with me, I began to parade around the school playground chopping, kicking, punching, and yelling, “Hi-yah!” as loudly as I could. Instead of warding off would-be attackers, all these antics did was earn me the name “Chuck.”

This was not what I had hoped for. In trying to imitate Daniel Larusso’s training from Mister Miyagi, I thought I could take up the role of school hero and karate champion. Instead, I was the class weirdo, and, as a cool as being called “Chuck” today might seem, to a second-grader, it was decidedly not cool.

Ever since, the idea of imitating someone worries me. I’m afraid it will backfire and give me a bad reputation. What if I earn another odd nickname that will make me the butt of more jokes and ridicule? I think that’s why many people struggle with growing as a Christian.

WHAT’S IN A NICKNAME?

We are, so to speak, trying to become who we are not. And it’s obvious—we are not Christ. We don’t behave like Christ, we don’t love like Christ, we don’t sacrifice like Christ. And that makes it difficult for us because if we are not Christ then becoming like Christ seems foolish and doomed to failure. In the big picture, no one wants to earn the life-long nickname “loser.”

Yet, that’s the reality of the name that we possess by faith. If you are a follower of Jesus, then you have been given a nickname that speaks to your identity: Christian. The name itself is so familiar today we might forget it was used as a derogatory term for the earliest disciples. “Christ-people,” or “little-Christs,” was what the on-looking world used to call those first followers of The Way who were looking to imitate Jesus in all of life. And it is in that name we find who we are really are becoming—Christ-people.

The name “Christian” stands as the doorway into this new identity. True spiritual formation must recognize this reality. To be truly “Christian” means entering through the door of Christ (John 10:7). For the Christian, growing spiritually requires that we grow in Christ. So not only is Christ the entry-point of our spiritual journey, but he is also the culmination of our spiritual path.

WHAT IT MEANS—REALLY MEANS—TO BE A CHRISTIAN

In perhaps the clearest job description of a pastor, the Apostle Paul sets out the goal of the Christian life. Within the church we labor together “until we all reach unity in the faith and in the knowledge of God’s Son, growing into maturity with a stature measured by Christ’s fullness” (Eph. 4:13). True spiritual formation is marked by maturity in Christ. Another way to say this is the goal of spiritual formation is to become like Christ.

This goal of spiritual formation, to become like Christ, is spoken of throughout the Scriptures. Paul says in 2 Corinthians 3:18, “we all, with unveiled faces are being transformed into the same image [Christ] from glory to glory.” The writer of Hebrews exhorts us to “run with endurance the race that lies before us, keeping our eyes on Jesus, the source and perfecter of our faith” (Hebrews 12:1-2). The identity of Christ will firmly and forever be fixed on the people of God.

This is nothing new within the teaching of church history. Christianity has long taught that true maturity and development is contained in becoming like Christ. Athanasius, one of the early church Fathers declared that Christ became a human so that humanity could become like Christ.[1] Calvin said, “the end of regeneration is that Christ should reform us to God’s image.”[2] In more recent days, one Biblical scholar has stated, “The glorified Christ provides the standard at which his people are to aim.”[3] Our trajectory, as Christians is to be conformed to the image of Christ (Rom. 8:29).

We must start with Christ as the entry point to truly being Christian, and the goal is to be like Christ as the culmination of his work within us. So how do we get there? What are the means by which cultivate the image of Christ within us?

YOU BECOME WHAT YOU BEHOLD

Paul writes in Colossians, “just as you have received Christ Jesus as Lord, continue to live in him, being rooted and built up in him and established in the faith” (Col. 2:6). Therein lies the whole arch of becoming like Christ: we begin in Christ, we continue in Christ, we are transformed to be like Christ. The means of Christlikeness is Christ himself. If Christ is the means to growing Christlikeness, then we are only changed inasmuch as we are looking to Christ, or beholding Christ.

The deeper we view, look at, and watch Christ, the deeper we are changed. “We all, with unveiled faces, are looking as in a mirror at the glory of the Lord and are being transformed into the same image from glory to glory; this is from the Lord who is the Spirit,” (2 Cor. 3:18) writes Paul to the Corinthian church. As we look at the glory of Christ, we are transformed into the very same glory we are observing. Christlikeness comes from fixing our eyes on Christ for all of life.

Looking at Christ will devastate us because it will show us how unlike Jesus we truly are. We’ll see our brokenness, our need, our evil and vile hearts. If we’re sensitive to this devastation, we’ll be capable of repentance and crying out for grace. If we’re hardened by the distance between ourselves and Christ, we’ll turn away and fail to behold Christ any further.

Yet as we look and are humbled to repentance, we will also be transformed. We will see the grace, mercy, and goodness of Christ. We will long to follow and trust him. We’ll demonstrate true faith as we embark upon the calling and formation he has for us. As our faith grows, we will look more and more at Christ and at the day of our last breath, when we will depart this life and finally enter into glory alongside Christ.

Beholding turns into Becoming that leads to Being.

PATTERNED AFTER CHRIST

Perhaps, this is the one place we do want to take up an imitation of someone. More than trying to be the Karate Kid, imitating Christ can transform our lives. As we behold, we will receive a new nickname. The name itself might be scandalous to the world, but beautiful to the Savior who gives it to us by his grace.

Maybe as we come to Christ and behold Christ and imitate our lives after Christ we will enjoy fully the moniker “Christ-people” or, simply “Christian.”

Jeremy Writebol is the Executive Director of GCD. He is the husband of Stephanie and father of Allison and Ethan. He serves as the lead campus pastor of Woodside Bible Church in Plymouth, MI. He is also an author and contributor to several GCD Books including everPresent and Make, Mature, Multiply. He writes personally at jwritebol.net. You can read all of Jeremy’s articles for GCD here.

[1]. Paraphrased from On the Incarnation

[2]. John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion & 2, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles, vol. 1, The Library of Christian Classics (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 189.

[3]. F. F. Bruce, The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1984), 350.

Missing the Spirit for His Gifts

The Holy Spirit. Three words couldn’t divide the church more. I suppose “I hate you” is up there, but that’s more of a division between people rather than churches.

Entire swaths of Christianity have divided over the third person of the Trinity. This division, over the place of the Spirit in the Trinity, left the Eastern Church (Orthodox) on one side and the Western Church (Roman) on the other, which, among other factors, eventually led to what was called the Great Schism.

DOCTRINE DIVIDES

Doctrine does divide. Attempting to forge unity, I’ve heard some people say, “Doctrine doesn’t matter.” Typically, they mean if we would all lay down our doctrines and just focus on Jesus, we would all get along.

But that assertion is also doctrinal. It’s saying to everyone else, if you lay down what you hold dear, and believe in the Jesus-only doctrine I consider precious, then we can all get along. This approach is well meaning but exclusivist, privileging its own view. It also leaves out the Father and the Spirit. We need to dig deeper. Why does doctrine over the Holy Spirit divide?

The fault line of division over the Spirit today is quite different from that of the early Church. The “great schism” affecting most of the modern church is over the gifts rather than the person of the Spirit. The division falls rather neatly along just a few of the Spirit’s more effusive gifts, things like speaking in tongues, prophecy, healings, and miracles.

TAKING SIDES

To simplify it for the moment, there are charismatics who treasure and practice these gifts, and cessationists who adamantly insist most of these gifts are no longer in effect. The groups shore up, take sides, and accuse one another of wary extremes. Some remain in the middle, self-described “open-but cautious.” Entire denominations, seminaries, and churches divide over their views of these gifts of the Spirit.

Wherever you fall in this debate, I think there’s a deeper issue at stake. It’s interesting that we don’t divide over spiritual gifts like service and mercy. We don’t part company over whether mercy is still in effect or if service is still valid. And there aren’t too many divisions over faith, hope, and love, what Paul called “the higher gifts” (1 Cor 12:31). Everyone believes in those.

Maybe, just maybe, we’re fighting over the wrong gifts. Certainly, there are things worth debating. Paul opposed Peter for his gospel-compromising racism. But what is the greater issue at stake here?

MISSING THE SPIRIT FOR HIS GIFTS

Quibbling over a few of the Spirit’s choice gifts, we’ve missed the most important gift of all—the Holy Spirit himself.

Pigeonholing the Spirit based on a few of his gifts is like sizing someone up after a single conversation. I’m not a big Quentin Tarantino fan. His films are too violent for me. I’ve seen clips here and there, and at the behest of several friends I did watch Inglorious Basterds. I’ll admit the initial interrogation scene is riveting, but I still find the flippant ultraviolence deplorable. So my initial impression of Tarantino was not positive, but that was before I met him in person.

One afternoon as my wife and I were waiting to be seated in a hole-in-the-wall Mexican restaurant, I glanced over the hostess’s shoulder. Recognizing a guy sitting by himself in the bar, my wife turned to me and said, “Honey, I think we were in college ministry with that guy.” I smirked and said, “Honey, that’s Quentin Tarantino.” Lunch was dominated by debate over whether we would introduce ourselves to Tarantino after we were done. My wife won the debate, so we walked over to say hi.

To my surprise, Tarantino was quite affable. He asked our names. My wife made a quip about having a guy’s name, and when Tarantino heard her name is Robie, he leaned in. He asked how she got the name. As Robie told the story, Tarantino tracked the plot, asked questions, and laughed along the way with two complete strangers. After a bit more chit-chat, he invited us to stay for a drink. We gratefully declined, but I walked away shocked by how kind and inviting he was. Based on his filmography, I figured he’d be a total jerk. If I’d stuck with my initial impression of Tarantino, I would have been wildly wrong.

GETTING TO KNOW THE SPIRIT

Sizing the Holy Spirit up based on a few of his gifts is a big mistake. If we relate to the Spirit primarily regarding miraculous gifts, and whether they are operative today, we distort and limit our understanding of the third person of the Trinity. He should be known for much more.

Who is the Spirit? Is he a person or a spiritual force? How are we meant to relate to him? Can we pray to the Spirit? Can we worship the Spirit? What is his role in creation? Is he present in culture? What will he do in the future? And what does being filled with the Spirit look like after all?

These are some of the questions I address in Here in Spirit. Instead of relating narrowly to the Holy Spirit, I’d like to broaden our engagement with him by touring aspects of his vast character that are often unexplored. In focusing more on who the Spirit is, we may find ourselves less divided.

Taken from Here in Spirit by Jonathan K. Dodson. Copyright (c) 2018. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com.

Jonathan K. Dodson (MDiv, ThM) is the founding pastor of City Life Church in Austin, Texas, which he started with his wife, Robie, and a small group of people. He has three great children and is also the founder of Gospel-Centered Discipleship. He is also the author of Here in Spirit: Knowing the Spirit who Creates, Sustains, and Transforms Everything; Gospel-Centered Discipleship, The Unbelievable Gospel: Say Something Worth Believing. He enjoys listening to M. Ward, smoking his pipe, watching sci-fi, and going for walks. You can find more at jonathandodson.org.

10 Ways to Identify True Grace

We talk about grace a lot. We preach grace from the pulpit, say grace from the table, and strive to stay in each other’s good graces. “Grace” is one of the richest words in our Christian vernacular, and yet, that’s often all it remains—a word. But is grace more than something we confess in a statement of faith? Is it more than just a word on our worship screens or in our vernacular?

Thomas Brooks was a man who not only talked about grace; he lived it. He felt the power of God’s grace and saw the effects of it in his life. His book, Precious Remedies Against Satan’s Devices, identifies the various schemes of Satan and the ways Christians fight against them. But just as much, Brooks hopes the reader catches a glimpse of the true grace of God—a grace that does something.

For Brooks, grace was more than a theory. It was real. It was visible and visceral. He notes that one of Satan’s primary devices for keeping Christians in a state of despair and doubt about their faith is “suggesting to them that their graces are not true, but counterfeit.”

Certainly, for us to feel that we have been “duped” by grace that’s not really there would be devastating to our faith. But God desires that we live in assurance, knowing that if we belong to Christ, nothing can separate us from Him (Rom. 8:38-39).

TEN WAYS TO IDENTIFY “TRUE GRACE”

To really live in grace, we must learn to distinguish what Brooks calls “true grace” from a false imitation. So how do we tell the difference between the two? Luckily, Brooks provides ten particulars that help us better define what true grace is. Here are Brooks’ ten statements with some personal commentary:

“True grace makes all glorious within and without.” Grace is a transformative reality. It does not leave us unaffected or stagnant, but like the breath God breathed into Adam, it rouses and awakens us to a new life. True grace, Brooks argues, is not like a lion becoming caged, where his environment or circumstances change but his nature does not. It is rather like the lion becoming a lamb. Our nature is made new by grace. The old is gone, and the new has come (2 Cor. 5:17).

“The objects of true grace are supernatural.” When we have been captured by true grace, our motivations and affections move to supernatural objects. Having a changed nature, we also have a changed allegiance, a changed mission, and a changed perspective on what the world can offer us. We now, by God’s transforming grace, seek a kingdom that is not of this world (John 18:36), treasures hidden in jars of clay (2 Cor. 4:17), and crowns of glory not made by human hands (1 Pet. 5:4).

“True grace enables a Christian, when he is himself, to do spiritual actions with real pleasure and delight.” Grace transforms internally, but it does not stop there. Grace changes us at the level of our actions. We do not act a new way merely because it’s our duty, but rather, because we delight to act in response to the grace we’ve been shown. Our service is not a burden but a joy to be spent for the souls of others (2 Cor. 12:15).

“True grace makes a man most careful, and most fearful of his own heart.” Grace has a way of turning our focus off of the shortcomings and defects of others. It levels the playing field. None can claim superiority to another in light of grace (Eph. 2:8-9). Grace does not jump to conclusions or make snap judgments.

“Grace will work a man’s heart to love and cleave to the strictest and holiest ways and things of God, for their purity and sanctity, in the face of all dangers and hardships.” There is a cost associated with following Jesus. We face internal pressure from our sin nature to put back on the old self and external pressure to cave to the world and all its opposition. But grace beckons us to behave in the world “with simplicity and godly sincerity” (2 Cor. 1:12).

“True grace will enable a man to step over the world’s crown, to take up Christ’s cross; to prefer the cross of Christ above the glory of this world.” Apart from grace, life is a quest to prove our worth and chase achievement. But because of grace, we have the freedom to boast in Christ alone. He makes us worthy. Our achievement is this: God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do (Rom. 8:3). We don’t need the world’s fool’s gold; we have an imperishable inheritance.

“Grace puts the soul upon spiritual duties, from spiritual and intrinsic motives…that doth constrain the soul to wait on God.” When our enemies Immediacy and Efficiency tempt us to despair, we have grace in our corner to remind us that Jesus declared from the cross, “It is finished” (John 19:30). What’s more, the work he gives us to do, he is bringing to completion in his time (Phil. 1:6). This does not depend at all on our impressiveness. Grace frees us to wait on him.

“Grace will cause a man to follow the Lord fully in the desertion of all sin, and in the observation of all God’s precepts.” We kill sin and follow the law because we have been given the privilege to do so. The wages of sin is death, and we came into the world totally bankrupt (Rom. 6:23). But now, because of grace, not only have our debts been paid—but we also have the opportunity to live righteously, with our whole hearts.

“True grace leads the soul to rest in Christ, as his chiefest good.” Grace enables us to draw near to our Lord’s throne with confidence and comfort (Heb. 4:16). Without grace, we would have every reason to be on edge, anxious, and fearful. But His love has cast out fear (1 John 4:18). His grace is a deep breath to the weary Christian.

“True grace will enable a soul to sit down satisfied and contented with the naked enjoyments of Christ.” Grace does not leave us lacking. We are like the sheep laid beside still waters by our Shepherd; we shall not want (Ps. 23:1). He is our Daily Bread and Living Water. Grace is unmerited favor, and it not only feeds the soul but fills it. It does not need to be dressed up. Grace alone is enough.

BLESSED ASSURANCE

Believer, do you find it hard to have confidence and assurance that you stand approved before God? Are you wondering what God thinks of you and whether or not you’re doing this Christian life the right way? How the grace of God has affected a person can tell you a lot about their spirituality.

If you’re finding yourself struggling to be sure of God’s grace in your life, run a diagnostics test. Ask yourself these questions:

- Has grace transformed your nature?

- Has grace changed your perspective?

- Has grace changed your actions?

- Has grace made you look inward?

- Has grace created a desire for holiness in your heart?

- Has grace freed you from having to prove your worth?

- Has grace caused you to wait on God in your life?

- Has grace made obedience to God a delight?

- Has grace allowed you to rest in Christ’s finished work?

- Has grace grown your contentment in Christ?

Your answers will help you determine what grace is really up to in your life.

GRACE IS NOT GRAY

A final note on grace that we cannot leave unnoticed as it relates to our assurance: When Jesus died for sinners, he did not do so in part. The grace found in salvation does not vary from person to person. Calvary eliminated the gray area. There is no one who has lived a good enough life or been a good enough person to make them “sort-of” righteous. And there is no one who has been justified and forgiven who will only have access to some of God’s grace. There is no scale from zero to ten that determines how much grace we’ve been shown; it is either a zero or a ten.

It’s fitting to close with one more word from Brooks:

“We have all things in Christ, and Christ is all things to a Christian. If we be sick, he is a physician; if we thirst, he is a fountain; if our sins trouble us, he is righteousness; if we stand in need of help, he is mighty to save; if we fear death, he is life; if we be in darkness, he is light; if we be weak; he is strength; if we be in poverty, he is plenty; if we desire heaven, he is the way.”

Zach Barnhart currently serves as Student Pastor of Northlake Church in Lago Vista, TX. He holds a Bachelor of Science from Middle Tennessee State University and is currently studying at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, seeking a Master of Theological Studies degree. He is married to his wife, Hannah. You can follow Zach on Twitter @zachbarnhart or check out his personal blog, Cultivated.

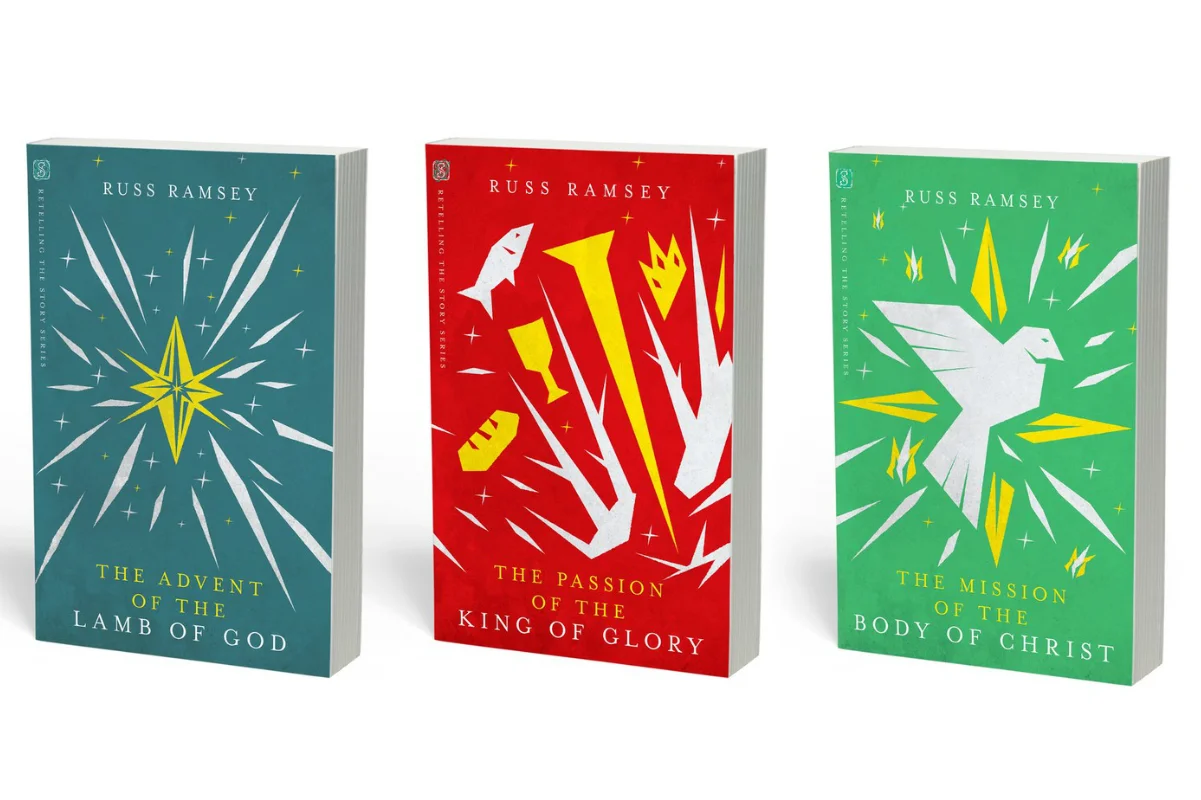

Retelling the Ascension Story

Three days after Jesus was buried, he rose from the grave and appeared to his disciples. Over the course of the next forty days, the resurrected Jesus, with his nail-pierced hands and spear-split side, spent time in the company of his friends—teaching them, encouraging them, and preparing them for a mission to take the story of his resurrection to the furthest reaches of the globe. On one of those occasions, as Jesus was eating with his friends, he told them to wait for the gift the Father had promised—the Holy Spirit Jesus had told them about. The Holy Spirit would come and comfort them and lead them forward. They were to remain in Jerusalem until this happened.

JUST WAIT HERE

It could not have been easy for the disciples to sit with their risen Lord. For as much joy and hope as Jesus’ resurrection brought them, they had been present at his death. They had witnessed the brutal execution of this man they loved, followed, and gave their lives to serving. They saw his beaten and bloody form hang from the cross as he breathed his last. After he died, they were hollowed out with grief.

Along with their grief was the guilt. The trauma of the crucifixion had revealed weaknesses in each one of them. They watched their loyalty to Jesus collapse under the weight of the chief priests’ resolve to put an end to what he had started. Not one of them had shown the strength they believed they possessed when Jesus was taken into custody. Each one denied knowing him in his greatest hour of need.

On top of the grief and the guilt was the fact that the world as they knew it had changed. When the resurrected Jesus appeared to his disciples, it was to remind them of their call to be his witnesses in the world. But after the resurrection, they hardly knew what that world was anymore.

They were fragile and unsettled, but they could not escape the reality that Jesus had in fact risen. And they knew they were somehow tied up in it. How could they not be? In a world where everyone dies, one man’s resurrection becomes instantly relevant to all. His resurrection was part of their story.

The disciples used that time to ask questions of Jesus. They wanted to understand what would happen next. Would he deal with the religious leaders who opposed him? Would he overthrow Rome? Would he restore the kingdom of Israel to her former glory? And if so, when? Would they be part of it?

THE COMING POWER

Jesus told them the Father was establishing his kingdom, but the particulars of this business were not theirs to know. Such knowledge belonged to God alone. What he could tell them, however, was that the Holy Spirit would come on each one of them in a matter of days, and when he did, they would be filled with power.

In that power, they would be his witnesses in Jerusalem, in Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth. This Great Commission, the disciples came to understand, was very much about the kingdom of God. Their mission, though they struggled to grasp it, was in some way the work of building the kingdom of God. The Holy Spirit and the kingdom of God—the two main subjects Jesus discussed after his resurrection—were inseparably linked, meaning the disciples’ call to bear witness to Christ carried eternal significance.

Forty days after the resurrection the disciples were on the Mount of Olives and Jesus was with them. He told them they would be his witnesses, and after he said this, he began to rise up into the sky right before their eyes. Up he went, until a cloud hid him from their sight. The disciples stood in silence as they watched him go. In that moment the world became an even greater mystery than the one the resurrection demanded they embrace.

Jesus did not need to visibly ascend. What the disciples witnessed was not for Jesus’ benefit but for theirs. He did it so they would know he was actually gone. They would not see him the next day. He would not attend to them in the same way he had these past forty days. They were not to wait for him. Now they were to wait for the Holy Spirit.

As the disciples stood, looking up and watching their friend vanish, two angelic beings dressed in white appeared. The luminous apparitions said, “Men of Galilee, why are you standing here looking into the sky? This same Jesus who has now been taken up will come again. He will descend in the same way you saw him ascend into heaven. He is coming back.”

But as far as the disciples were concerned, the time for standing around and looking up to heaven had passed. They needed to let Jesus go and step into the mission he had given them. What was happening in the sky was not their chief concern. What was happening on earth was.

The disciples responded by obeying Jesus’ command to wait. They left the Mount of Olives and went back into Jerusalem and gathered many of Jesus’ followers together in the upper room where they were staying.

USING THE TIME

More than 120 people were gathered in all. There were the eleven disciples: Simon Peter, James and John (the sons of Zebedee), Peter’s brother Andrew, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew, Matthew the tax collector, Simon the zealot, Alphaeus’s son James, and James’s son Judas. With them were the women who had discovered the empty tomb, Jesus’ mother, Mary, Jesus’ brothers, and many more whose lives had been changed by Jesus.

For ten days they waited, but it was not a passive waiting. They used the time. They joined together to pray. They prepared for the work that lay ahead. This was an act of obedience to their slain and risen Lord. In their waiting they trusted him, even though their understanding of what lay ahead was less than clear.

Jesus never told them how long they would have to wait for the Holy Spirit to come—just that he would arrive in a little while. After all that had transpired in Jerusalem in recent weeks, remaining there was as much an act of courage as it was an act of faith. This was the city where Jesus had been arrested, beaten, crucified, and buried. This was the place where Judas had betrayed Jesus for a pocket full of silver and where Peter had denied knowing Jesus for fear of a child’s accusation. This was the city that seemed bent on erasing any trace of the movement Jesus started.

There were more appealing places to wait and families many of them could have gone home to. Each had the option to return to their homes in places like Galilee, Nazareth, and Cana. They could have gone back to their old jobs—fishing, collecting taxes, carpentry, prostitution. They could have even gone back to their old religions—Judaism or Roman paganism. But those who gathered in the upper room didn’t. They chose to obey Christ, and they waited. And they used their time.

THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE KING

Each person gathered in that upper room over the course of those days had been changed in some way through their relationship with Jesus. The cast of characters would have included people like Mary Magdalene, who had once been possessed by demons, and Nicodemus, the Pharisee who helped cover the cost of Jesus’ burial. Perhaps the synagogue ruler from Capernaum, Jairus, was there with his daughter Talitha, whom Jesus had raised from the dead, and perhaps they were huddled together in friendship with Lazarus, whom Jesus had also raised from the dead. Former lepers, newly sighted blind people, and once-paralyzed beggars would have been milling about in the crowd too.

As it has always been with the people of God, their desire to obey Christ was strengthened by the bond of their fellowship with one another. God had made them to need one another—to be known, loved, and supported. This was the power and influence of Jesus in each of their lives. He had loved and served them in such a way that they had come to need one another. The usual dividing lines of the day—wealth, nationality, reputation—were already beginning to blur. These were people who had come to accept that they were all weak and that Jesus had been strong for them. They were all poor and Jesus had been generous with them. They were all outsiders and Jesus had given them a place with him. These truths drew them toward one another.

Taken from The Mission of the Body of Christ (Retelling the Story Series) by Russ Ramsey. Copyright (c) 2018 by Russ Ramsey. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com.

Russ Ramsey and his wife and four children make their home in Nashville, Tennessee. He is the author of Struck, Behold the Lamb of God, and was awarded the 2016 Christian Book Award from the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association for his book Behold the King of Glory. Russ grew up in the fields of Indiana and studied at Taylor University and Covenant Theological Seminary (MDiv, ThM). He is a pastor at Christ Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, and his writing has appeared at The Rabbit Room, The Gospel Coalition, The Blazing Center, and To Write Love on Her Arms.

Unquenchable Love and Unconquerable Hope

In this you rejoice, though now for a little while, if necessary, you have been grieved by various trials, so that the tested genuineness of your faith—more precious than gold that perishes though it is tested by fire—may be found to result in praise and glory and honor at the revelation of Jesus Christ. Though you have not seen him, you love him. Though you do not now see him, you believe in him and rejoice with joy that is inexpressible and filled with glory, obtaining the outcome of your faith, the salvation of your souls. (1 Pet. 1:6–9)

The year 2016 marked the centennial anniversary of America’s National Park Service. In celebration of the anniversary, a particular issue of National Geographic contained some amazing photos of several parks—as only National Geographic can capture. Now, I pride myself on having a Jed Bartlet-like appreciation for the national parks, so when I looked at these photos, I was captivated. They were unlike anything I had seen. In a single image, you could see both day and night, shadow and light, sun and moon. The photographer, for hours at time, took thousands of pictures, and with the aid of technology, “compressed the best parts into a single photograph.” The result is a massive and sweeping image comprised of thousands of smaller photos.[1] Yet, the more I looked, the less certain I was that I liked it. For these photos are attempts at seeing what is not meant to be seen— a full day all at once. The scenery was beautiful, yet odd. It was unnatural. Frankly, it wasn’t real.

When we face trials for which we don’t know the outcome or don’t understand the purpose, and struggle with wanting to know all the answers at once, it is like we are wanting to see a full photo of the end and the beginning, in one frame. But were we to see such, I think we would be disappointed. It likely wouldn’t make sense, for it is neither real nor what God intends. God, in his kindness and wisdom and mercy, uses trials and hidden things to draw us closer to himself, and even when we can’t understand the outcome or the purpose, joy is revealed in the process.

After Peter reminded his exiled readers that they have a living hope in a God who has saved them and will strengthen and sustain them to the end, he turns to address their trials and suffering.[2]

THE END OF SUFFERING

When enduring the onslaughts of a cynical age, we’ve seen how looking in to find Christ Jesus, our living hope, cannot only sustain until the end of time, but also provide strength for the present. Peter rightly acknowledges that this kind of reliance will lead to joy, much like the supportive James 1:2 that instructs believers to “count it all joy” in the face of trials. With the end still in view, Peter also reminds that these trials are only “for a little while” (1 Pet. 1:6). This is not Peter’s attempt to minimize them or belittle the pain and challenges they produce, but to offer another bolster of hope that even the longest of trials will, in fact, end. Trials and sufferings are a part of a post-Genesis 3 world. They were not what God intended when he created the world. Whether the result of sin, physical malady, or material loss, trials and sufferings do not escape the believer in Christ (John 16:33) and, indeed, can serve as painful instruments of the evil one.

As we behold and experience the trials that are a shared burden in this world, believers often understandably question why God allows such to happen. Even though God, in his faithfulness and wisdom, may never allow his children to have the full understanding of why he permits suffering, Peter’s words here give a great deal of insight and help. Trials, of all kinds, test our faith in crucible-like ways—ways that will show the greatness and goodness of God and result in our greater praise to him. This is, in part, because he endures the trials with us. The living hope we have of Christ himself within us is even better than the appearance of an additional man alongside Daniel’s three friends in the fiery furnace (Dan. 3:25). Through Christ, in every trial we have a shield of faith “with which you can extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one (Eph. 6:16). When we are tempted, God is faithful and “will not let you be tempted beyond your ability, but . . . will also provide the way of escape” (1 Cor. 10:13).

Often the way to rejoicing is the way of weakness through suffering, and a powerful New Testament portrait of this is the life of the apostle Paul revealed in 2 Corinthians. As J. I. Packer explains in is marvelous book Weakness Is the Way, the testimony Paul gives shows

"pain and exhaustion, with ridicule and contempt, all to the nth degree; a tortured state that would drive any ordinary person to long for death, when it would all be over. But, says Paul, Christ’s messengers are sustained, energized, and empowered, despite these external weakening factors, by a process of daily renewal within."[3]

Paul begins 2 Corinthians declaring that “we felt that we had received the sentence of death. But that was to make us rely not on ourselves but on God who raises the dead” (2 Cor. 1:9). From this reliance comes “good courage” (2 Cor. 5:6) and the ultimate lesson that God’s “power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9).